Background

Health security, an inherent human right for all, faces its greatest adversary in armed conflicts, often leading to public health emergencies that necessitate robust health systems (1). With the rise of protracted conflicts, 300 million people require humanitarian aid, and the need to alleviate human suffering swiftly becomes critical. Modern warfare systematically targets health systems and other security facets, making the attainment of interdependent Sustainable Development Goals such as health, development, and peace utopic (2). Confronting these challenges, diplomacy and humanitarian intervention assume a critical role. Experts argue that negotiation is indispensable in humanitarian efforts, especially with the increasing number of conflicting parties demanding diplomatic strategies (3).

To navigate these complexities for health systems strengthening a nuanced integrative approach is necessary. Humanitarian Diplomacy (HD) and Global Health Diplomacy (GHD) emerge as essential elements for addressing these challenges. HD facilitates negotiations to ensure humanitarian aid and safeguard rights during crises (4, 5), whereas GHD encompasses the confluence of humanitarianism and international politics, functioning as a framework for deliberating worldwide health priorities. Traditionally operating in siloes, protracted conflicts require a more integrated approach embodied in the Humanitarian-Development-Peace Nexus (HDPN) (6). The HDPN, or the Triple Nexus, emerges as a transformative approach to address protracted conflicts by harmonising immediate relief aid with sustainable development and peacebuilding efforts. Within this nexus, health systems have a dual role as both recipients and enablers of peace and development efforts (6).

In conflict settings, harnessing the synergies between HD and GHD is important. GHD offers a macro-level perspective, shaping policies for global governance and standards while HD ensures practical implementation. This article examines the relationship between HD and GHD and how they can improve health systems within HDPN. It also briefly examines how foresight, as a future-oriented discipline, can further enhance the HDPN framework, supporting the transformation of local health systems impacted by crises. By combining top-down policy directions with bottom-up humanitarian actions, a more sustainable and holistic approach to developing health systems in conflict settings can be achieved, preserving health rights for all.

Synergies and Challenges of Diplomacies

Humanitarian diplomacy (HD) definitions can be confusing. It is commonly defined in narrow or broad terms. The former views HD as advocating for aid access while adhering to neutrality, impartiality, and independence (7), while the latter involves negotiating with diverse actors in politicised environments driven by the imperative of humanity (8). Despite these nuances, a common thread in both definitions of dialogue and negotiations to facilitate principled humanitarian action for vulnerable populations exists but necessitates a unified understanding and standardised practice. Global Health Diplomacy (GHD) became an officially recognised concept after recognition by the United Nations General Assembly Resolution in 2009. It aims to improve health security and population health outcomes (9) by operating across three levels of diplomacy: core, multi-stakeholder, and informal (10).

The theoretical foundations of HD, incorporating Responsibility to Protect (R2P) and international cooperation, offer a flexible framework reflecting a global commitment to crisis prevention and humanitarian aid (3, 11). This broad application aligns with GHD in connecting health and peace by coordinating efforts across the public, private, and civil sectors to promote health and avert emergencies.

In practice, HD plays a vital role in peacekeeping by ensuring protection and access to humanitarian aid (12). Key diplomatic practices such as negotiation to access, establishment of ceasefires, paving the way for humanitarian corridors, and upholding international humanitarian law are essential for peacekeeping and HD (3). For instance, UNSCR 2533 provides humanitarian access in Syria, allowing health services to be delivered without interference (13). On the other hand, GHD facilitates negotiation of donor assistance with non-state and state actors, improvement of healthcare, introduction of humanitarian aid, and health and human security concerns in foreign policy, ultimately leading to state-building and peacekeeping (14). GHD aids in the development of health systems by repairing diplomatic failures in conflict regions. For instance, the United States trained medical personnel in Afghanistan and Syria, among other countries, as part of capacity-building efforts in the short and long term (14). Additionally, efforts to mitigate the health consequences of armed conflict include interventions such as immunisation campaigns (vaccine diplomacy) and humanitarian ceasefires (15).

This unified approach between HD and GHD paves the way for navigating complex environments, as shown in Figure 1. HD secures access and protection through various actors, including international actors or local civil society organisations, and GHD manages global health challenges and fosters security (16). However, challenges persist. HD and GHD sometimes face dilemmas in upholding neutrality and impartiality, especially when humanitarian actors are involved in human rights advocacy and peace negotiations (17) or when GHD navigates donor assistance in political contexts (14). Both fields confront the politicisation of aid, risking compromise in the impartiality of HD, and thus perceived as a tool for advancing international interests (8).

Figure 1. Diagram illustrating the overlap and distinction of roles for humanitarian diplomacy and global health diplomacy

The focus on politics in aid decisions raises concerns about susceptibility to manipulation under the guise of humanitarian operations, such as R2P (18). Similarly, GHD can be influenced by the broader foreign policy objectives of states (15). Consequently, GHD can be a means to further political and economic interests rather than building health systems.

Legal and ethical concerns emerge in HD when engaging with non-state armed groups (NAGs), some classified as terrorist organisations by states (19). GHD also faces challenges navigating international laws and regulations, especially when implementing health initiatives under economic sanctions or embargoes (15). Furthermore, in 2016, UN Security Council Resolution 2286 condemned attacks on healthcare workers and facilities, yet attacks in Syria, South Sudan, and Yemen persist (20, 21, 22). The politicisation of these fields undermines legitimacy and erodes societal trust, restricting efforts to rebuild health systems (20).

Overcoming challenges requires strengthening international cooperation, upholding neutrality and impartiality, navigating legal and ethical frameworks, and focusing on long-term solutions are crucial for HD and GHD. Furthermore, to counter politicisation, humanitarian principles must be reaffirmed. These principles should serve as a means of expanding the scope of functions when necessary. Synergising HD and GHD can significantly contribute to sustainable health systems, aligning with the broader objectives of the Humanitarian-development-peace Nexus (HDPN) (3).

Humanitarian-Development-Peace Nexus: A Transformational Paradigm

Overcoming challenges requires strengthening international cooperation, upholding neutrality and impartiality, navigating legal and ethical frameworks, and focusing on long-term solutions are crucial for HD and GHD. Furthermore, to counter politicisation, humanitarian principles must be reaffirmed. These principles should serve as a means of expanding the scope of functions when necessary. Synergising HD and GHD can significantly contribute to sustainable health systems, aligning with the broader objectives of the Humanitarian-development-peace Nexus (HDPN) (3).

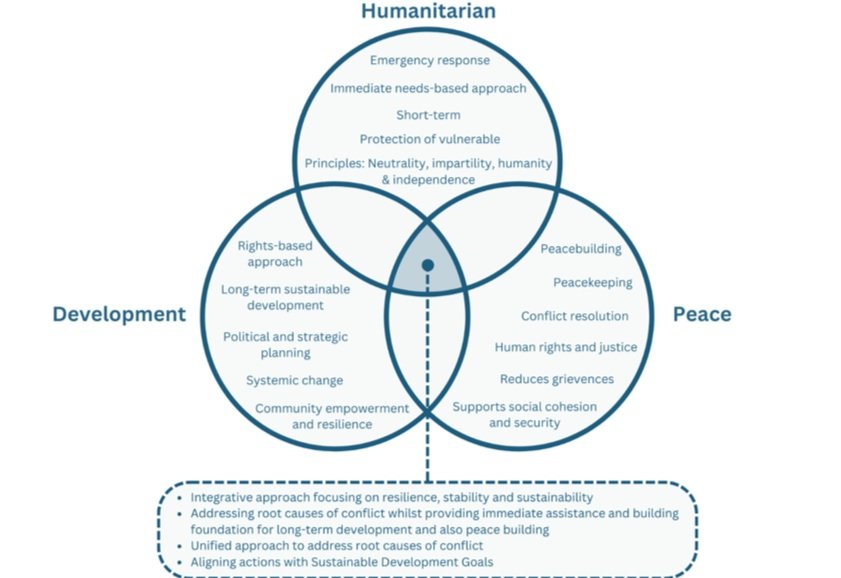

A key element to highlight in HDN is its future orientation. While humanitarian aid per se takes a needs-based approach in punctual short-term interventions that are guided by principles of humanity, neutrality, impartiality, and independence (26); it differs from development’s rights-based approaches and long-term goals (27). The peace element of the nexus includes peacebuilding (creating peace) and peacekeeping (maintaining peace) efforts to ensure conflict resolution, security, sensitivity, and stability (28), which also requires a futures thinking mindset to be realised. State building is central, as it supports the development of legitimate and accountable state institutions for security, justice, and basic services (29). Blending in these sectors has grown to address root causes, especially in their work in early recovery, preparedness, risk mitigation, conflict resolution, and peacebuilding (26).

Figure 2. Diagram illustrating the interconnectedness of the humanitarian, development, and peace domains

Strengthening health systems requires humanitarian actors to link emergency aid to sustainable care, avoiding local dependency on non-government organisations (NGOs) and promoting a person-centred approach (24). Furthermore, adding the peace element would reduce conflict-driven grievances and ensure equitable access to health services (30).

Within HDPN, health systems play a dual role. They benefit from reconstruction that contribute to overall recovery and development efforts. This process ensures sustainability by securing resources and prioritisation (31). Simultaneously, health systems enable peacebuilding. Health programs and workers significantly influence community resilience and social cohesion, offering avenues for dialogue and reducing violence. Strengthening health systems through HDPN supports the maintenance of development and peacebuilding gains through building institutions, infrastructure, and capacity (32). Moreover, emphasising localisation (local involvement) and community participation in health programmes under HDPN fosters ownership, acceptance, and safer healthcare access (31).

However, protracted conflicts often fragment healthcare provision strategies, execution, and coordination between development and humanitarian actors (33). Furthermore, there is reluctance among humanitarian actors and donors to strengthen health systems capacity, with limited involvement of development actors and inadequate financial resources, with a disproportionate focus on vertical humanitarian programs (urgent interventions) that often leads to short-term initiatives (33). To remedy this, the NWOW encourages a unified approach among development and humanitarian actors, although it lacks conceptual clarity, technical capacity, and stakeholder commitment (34).

The humanitarian health cluster should include developmental aspects such as long-term strategic planning and collaborative assessments in its operations involving multiple stakeholders in early recovery efforts. This includes humanitarian programming and health sector coordination, covering all stages from hazard to early recovery. International community and development actors must integrate these activities into their frameworks with well-defined funding structures and community empowerment to foster health ownership and longevity. To design and implement integrated humanitarian development programs, stakeholders must negotiate collective future-oriented goals and reflect on their progress. Finally, accountability, extending beyond funders to those affected by crises, remains a significant challenge, necessitating appropriate frameworks that ensure responsiveness (35). Figure 3 shows just a few examples of where HDPN has been employed.

Figure 3. Myanmar (6), Somalia (36), and Palestine (37) as examples where HDPN has been used

How foresight can enhance the HDPN and strengthen health systems?

Despite the undeniable importance of the Humanitarian, Development and Peace Nexus (HDPN), there is little research on how foresight capacities can enhance it and, ultimately, strengthen health systems. Foresight professionals possess a unique set of core competencies that enable them to identify patterns of change and trends essential for informed decision-making in long-term planning processes. Using foresight tools and frameworks, foresight professionals can efficiently monitor the environment and identify potential disruptions and their implications on humanitarian, development, and peace-building missions.

Foresight specialists also have a distinct ability to create and plan for multiple future scenarios. They craft preferred future visions, which help build capacity to achieve the long-term development and peace goals that are part of the HDPN nexus. By utilising foresight, HDPN can develop a more robust and resilient system that is better equipped to deal with future challenges and uncertainties, but also opportunities and the spotlight of localised innovations.

Foresight processes feed from participatory and community- or local-based efforts, an approach that also plays a key role in enhancing the HDPN's capabilities seeking to strengthen health systems, leading to more effective and efficient interventions that can better serve the needs of communities in crisis and conflict-affected areas around the world.

Framing it all together

To combat health challenges beyond medical services, diplomacy assumes a role in representation, communication, and negotiation (3). It holds socialising power, influencing the actors involved in conflict, including NAGs, for a more humane and nonviolent form (38, 39). A conceptual diagram is shown in Figure 4.

Damage to health systems during wars reduces medical facilities and the medical workforce. Consequently, chronic conditions go unmanaged, and if health services are not operational, then it can lead to higher death rates fuelled by shortages of basic supplies and food and crimes against humanity (15, 40). In such contexts, services such as operating theatres, epidemic control, medical care for victims, maternity wards, and other services will be placed (40).

To facilitate this, GHD allows for the mobilisation of stakeholders to address crises and establish peace, focusing on the implementation of humanitarian aid and prioritising health, addressing human security concerns that have a detrimental impact on health systems and disproportionately affect vulnerable populations. GHD has been used to promote dialogue and cooperation between opposing factions; for instance, in Afghanistan, the WHO-led polio eradication campaign served as an entry point for local-level diplomacy, allowing dialogue, strengthening health systems, and peace initiatives (41).

Additionally, HD ensures access to vulnerable populations for immediate relief, facilitating rehabilitation and development initiatives through humanitarian corridors and safe zones, and ceasefires instrumental safe delivery of medical supplies, setting up immunisation campaigns, and protecting health facilities (42, 43). These efforts maintain essential health service functionality and preserve it for health system recovery.

Within HDPN, both top-down organisations, such as the WHO and UN High Commission for Refugees, and bottom-up organisations, being local charities and civil services, can combine their efforts aligning humanitarian assistance brought about by bi- and multi-lateral organisations (26). Ultimately, this allows the integration of health intelligence, data sharing, and partnerships at different levels to strengthen health systems (15, 26).

Rebuilding health systems requires addressing the social determinants of health (18) and adopting a culturally sensitive person-centred approach. Community empowerment and capacity building will reduce dependency, ensuring continuity of health systems. This can be achieved by developing training programs. Furthermore, resource mapping can help identify assets and gaps in healthcare systems that are useful for resource allocation and planning.

Figure 4. Conceptual diagram illustrating the distinct and overlapping roles of Humanitarian Diplomacy and Global Health Diplomacy within the Humanitarian-Development-Peace Nexus for health systems strengthening

Finally, foresight presents itself as an additional ally discipline equipped with tools and methodologies that can better serve the future orientation of the HDPN framework and the need for a person-centred approach, ultimately leading to the transformation of local health systems affected by crises.

Conclusion: Future Directions

The shift from traditional forms of diplomacy to a more holistic integration of HD and GHD within HDPN marks a significant step towards achieving broader objectives in humanitarian action. This underlines the importance of foresight capacities in addressing the evolving challenges of health systems strengthening in protracted conflicts.

The complexity of conflicts is intensified by global trends such as widespread forced displacement, climate change, rising global inequalities, population growth, and rapid urbanisation, all of which increase vulnerability to conflicts. As these issues worsen, the scope of humanitarian crises expands. Understanding this in HDPN contexts shapes the strategies employed in HD and GHD.

Financial considerations are central to this dialogue, especially in the context of a globalised economy intertwined with conflict dynamics. Competition for resources and findings may increase, necessitating efficient financing mechanisms and resource allocation within the HDPN.

Navigating political complexities in international collaborations will remain challenging, requiring strategic diplomacy and commitment to uphold humanitarian principles. However, expanding these principles to achieve better health outcomes is a matter of discussion. There is a concerning trend of political motives overshadowing the HDPN, risking the integrity of humanitarian action, and leading to unintended consequences. We need to redefine the principles of humanitarian actors, but this does not happen without caveats. The expansion of these principles allows for broader activities and better application of humanitarian action, which requires a balance between pragmatism and humanitarian values.

Diversification of the humanitarian ecosystem is set to increase, especially under HDPN. Non-formal actors, such as military actors and diplomatic agents, will gain influence. The way this power is going to be used, with greater acceptance of activities outside their scope, will be dictated through their agenda. This also means that greater emphasis will be placed on producing frameworks of accountability and defining the scope for each actor. This will begin to challenge traditional operational models.

The roles of local actors and communities were set to expand within the HDPN framework. They are transforming from being passive recipients of aid to asserting their autonomy, rights, and identity. Empowerment is key to creating sustainable and culturally sensitive solutions. Furthermore, research and analysis should expect an increase in evidence generation for better-informed practices.

The stakeholder landscape is constantly evolving, requiring a greater need for coordination, information sharing, and collaborative frameworks. As information sharing becomes increasingly crucial, concerns regarding data security, privacy, and equitable access to information must be addressed through strong practices and policies.

Strengthening accountability measures and establishing monitoring frameworks to align with the needs of the population. There should be global recognition of humanitarian aid, not merely acting as a temporary short-term solution to conflict, but also as a facilitator for long-term state-building, sustainable development, and conflict resolution.

With its future orientation and commitment to resolving armed conflicts through diplomacy, the HDPN framework holds strong grounds for reducing suffering, building resilience and preparedness, and remedying underlying causes of conflict. It is with optimism that we envision a future in where health system strengthening leverages the collaborative nature and opportunities presented by combining HD and GHD within the HDPN.

References

1. Health-care needs of people affected by conflict: future trends and changing frameworks - The Lancet [Internet]. [cited 2024 Feb 2]. Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(09)61873-0/fulltext

2. United Nations General Assembly. Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development [Internet]. New York (NY): UN; 2015 Sep 25 [cited 2024 Dec 19] [Internet]. [cited 2024 Feb 2]. Available from: https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N15/291/89/PDF/N1529189.pdf?OpenElement

3. Bogatyreva O. Humanitarian Diplomacy: Modern Concepts and Approaches. Her Russ Acad Sci [Internet]. 2022 Dec [cited 2023 Dec 22];92(S14):S1349–66. Available from: https://link.springer.com/10.1134/S1019331622200047

4. Balzacq T, Charillon F, Ramel F, editors. Global Diplomacy: An Introduction to Theory and Practice. Springer Nature; 2019 Nov 8.

5. De Lauri A. Humanitarian diplomacy: A new research agenda. Cmi Brief. 2018;2018(4).

6. International Organization for Migration. The Humanitarian-Development-Peace Nexus in Health. July 2021. Available from: https://www.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl486/files/documents/HDPN-in-Health-External.pdf

7. Bennett J. Review. Dev Pract [Internet]. 2008;18(3):458–60. Available from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/27751945

8. Minear L, Smith H. Humanitarian Diplomacy: Practitioners And Their Craft.

9. Novotny TE, Kickbusch I, Told M. 21st century global health diplomacy. Singapore: World scientific; 2013. (Global health diplomacy).

10. Katz R, Kornblet S, Arnold G, Lief E, Fischer JE. Defining Health Diplomacy: Changing Demands in the Era of Globalization: Defining Health Diplomacy. Milbank Q [Internet]. 2011 Sep [cited 2024 Feb 2];89(3):503–23. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1468-0009.2011.00637.x

11. Simons G. Russian foreign policy and public diplomacy: Meeting 21st century challenges. Vestnik RUDN. International Relations. 2020 Dec 15;20(3):491-503.

12. Lauri AD. CMI Report, number 1, January 202. Prot Civ.

13. United Nations Security Council. Resolution 2533 [Internet]. New York: UN; 2020 Jul 13 [cited 2024 Jan 12] Avaliable from: http://unscr.com/en/resolutions/doc/2533.

14. Chattu VK, Knight WA. Global Health Diplomacy as a Tool of Peace. Peace Rev [Internet]. 2019 Apr 3 [cited 2024 Feb 2];31(2):148–57. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10402659.2019.1667563

15. Kickbusch I, Nikogosian H, Kazatchkine M, Kökény M. A GUIDE TO GLOBAL HEALTH DIPLOMACY.

16. Harroff-Tavel M. THE HUMANITARIAN DIPLOMACY OF THE INTERNATIONAL COMMITTEE OF THE RED CROSS.

17. Leebaw B. The Politics of Impartial Activism: Humanitarianism and Human Rights. Perspect Polit [Internet]. 2007 Jun [cited 2024 Feb 1];5(2):223–39. Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/perspectives-on-politics/article/abs/politics-of-impartial-activism-humanitarianism-and-human-rights/BBE7018F7927B94CE1FE28E95946668F

18. Peplow D, Augustine S. The Submissive Relationship of Public Health to Government, Politics, and Economics: How Global Health Diplomacy and Engaged Followership Compromise Humanitarian Relief. Int J Environ Res Public Health [Internet]. 2020 Feb 22 [cited 2024 Feb 2];17(4):1420. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/17/4/1420

19. Modirzadeh NK, Lewis DA, Bruderlein C. Humanitarian engagement under counter-terrorism: a conflict of norms and the emerging policy landscape. Int Rev Red Cross [Internet]. 2011 Sep [cited 2024 Jan 31];93(883):623–47. Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/identifier/S1816383112000033/type/journal_article

20. Druce P, Bogatyreva E, Siem FF, Gates S, Kaade H, Sundby J, et al. Approaches to protect and maintain health care services in armed conflict – meeting SDGs 3 and 16. Conflict Health [Internet]. 2019 Dec [cited 2024 Feb 1];13(1):2. Available from: https://conflictandhealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13031-019-0186-0

21. Security Council Adopts Resolution 2286 (2016), Strongly Condemning Attacks against Medical Facilities, Personnel in Conflict Situations | UN Press [Internet]. [cited 2024 Feb 1]. Available from: https://press.un.org/en/2016/sc12347.doc.htm

22. Taylor GP, Castro I, Rebergen C, Rycroft M, Nuwayhid I, Rubenstein L, et al. Protecting health care in armed conflict: action towards accountability. The Lancet [Internet]. 2018 Apr [cited 2024 Feb 1];391(10129):1477–8. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S014067361830610X

23. As World Humanitarian Summit Concludes, Leaders Pledge to Improve Aid Delivery, Move Forward with Agenda for Humanity | UN Press [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jan 30]. Available from: https://press.un.org/en/2016/iha1401.doc.htm

24. Administrator. World Health Organization - Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean. [cited 2024 Mar 8]. Humanitarian-development-peace nexus. Available from: http://www.emro.who.int/uhc-health-systems/health-systems-in-emergency-lab/humanitarian-development-peace-nexus.html

25. Realizing the triple nexus: Experiences from implementing the human security approach [cited 2024 Feb 2]. Available from: https://www.un.org/humansecurity/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/FINAL-Triple-Nexus-Guidance-Note-for-web_compressed.pdf [Internet]. [cited 2024 Feb 2]. Available from: https://www.un.org/humansecurity/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/FINAL-Triple-Nexus-Guidance-Note-for-web_compressed.pdf

26. O’Reilly G. Aligning Humanitarian Actions and Development. In: Aligning Geopolitics, Humanitarian Action and Geography in Times of Conflict [Internet]. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2019 [cited 2024 Feb 2]. p. 119–40. (Key Challenges in Geography). Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-030-11398-8_6

27. Lie JHS. The humanitarian-development nexus: humanitarian principles, practice, and pragmatics. J Int Humanit Action [Internet]. 2020 Dec 10 [cited 2024 Feb 2];5(1):18. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41018-020-00086-0

28. Barakat S, Milton S. Localisation Across the Humanitarian-Development-Peace Nexus. J Peacebuilding Dev [Internet]. 2020 Aug [cited 2024 Jan 25];15(2):147–63. Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1542316620922805

29. Fanning E, Fullwood-Thomas J. The Humanitarian-Development-Peace Nexus: What does it mean for multi-mandated organizations?.

30. World Health Organization. WHO Thematic Paper on Health and Peace. In: 2020 Report of the Secretary-General on Peacebuilding and Sustaining Peace; 2020. [cited 2024 Mar 8].

31. Talisuna A, Mandalia ML, Boujnah H, Tweed S, Seifeldin R, Saikat S, et al. The humanitarian, development and peace nexus (HDPN) in Africa: the urgent need for a coherent framework for health. BMJ Glob Health [Internet]. 2023 Oct [cited 2024 Mar 10];8(10):e013880. Available from: https://gh.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/bmjgh-2023-013880

32. WHO Global Health and Peace Initiative (GHPI) [Internet]. [cited 2024 Mar 10]. Available from: https://www.who.int/initiatives/who-health-and-peace-initiative

33. Dureab F, Hussain T, Sheikh R, Al-Dheeb N, Al-Awlaqi S, Jahn A. Forms of Health System Fragmentation During Conflict: The Case of Yemen. Front Public Health [Internet]. 2021 Jul 12 [cited 2023 Nov 11];9:659980. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2021.659980/full

34. United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, Policy Development and Studies Branch. New Way of Working. Geneva: OCHA, PDSB; 2017. Available from: www.unocha.org.

35. Olu O.O., Usman A., Nabyonga-Orem J. Recovery of health systems during protracted humanitarian crises: A case for bridging the humanitarian-development divide within the health sector. BMJ Glob Health [Internet]. 2023;8(6):e012998. Available from: https://gh.bmj.com/

36. policy_brief_humanitarin_development_peace_nexus_and_its_relevance_to_health_sector-2.pdf.

37. Aviles S. ILO Arab States' Strategic Engagement in the Humanitarian-Development-Peace Nexus: Challenges & Opportunities. Geneva: International Labour Office; June 2023. [Internet]. Available from: https://www.ilo.org/beirut/publications/WCMS_888462/lang--en/index.htm

38. Sharp P. Mullah Zaeef and Taliban Diplomacy: An English School Approach. Rev Int Stud [Internet]. 2003;29(4):481–98. Available from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20097871

39. Toros H. `We Don’t Negotiate with Terrorists!’: Legitimacy and Complexity in Terrorist Conflicts. Secur Dialogue [Internet]. 2008 Aug [cited 2024 Feb 1];39(4):407–26. Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0967010608094035

40. Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) International [Internet]. [cited 2024 Feb 1]. War and conflict in depth | MSF. Available from: https://www.msf.org/war-and-conflict-depth

41. Ozano K, Martineau T. Responding to Humanitarian Crises in Ways That Strengthen Longer-Term Health Systems: What Do We Know. ReBUILD Consortium. 2018. [Internet]. Available from: https://www.rebuildconsortium.com/resources/responding-to-humanitarian-crises-in-ways-that-strengthen-longer-term-health-systems-what-do-we-know/

42. The ICRC and the “humanitarian–development–peace nexus” discussion: In conversation with Filipa Schmitz Guinote, ICRC Policy Adviser. Int Rev Red Cross [Internet]. 2019 Dec [cited 2024 Mar 8];101(912):1051–66. Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/identifier/S1816383120000284/type/journal_article

43. Pattanshetty S, Bhatt K, Inamdar A, Dsouza V, Chattu VK, Brand H. Health Diplomacy as a Tool to Build Resilient Health Systems in Conflict Settings—A Case of Sudan. Sustainability [Internet]. 2023 Sep 12 [cited 2024 Mar 8];15(18):13625. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/15/18/13625