My name is Juan Sebastian Brizneda. Bold way of starting an article, right? Well, my intention is to state some opinions argued and based on personal experiences I have had. I truly believe that you should be honest with the public who you’re talking to.

I am 25 years old and I was born and raised in Bogota, Colombia. However, between work and studies I have been living throughout Western Europe for the past two years: Italy, Switzerland and France.

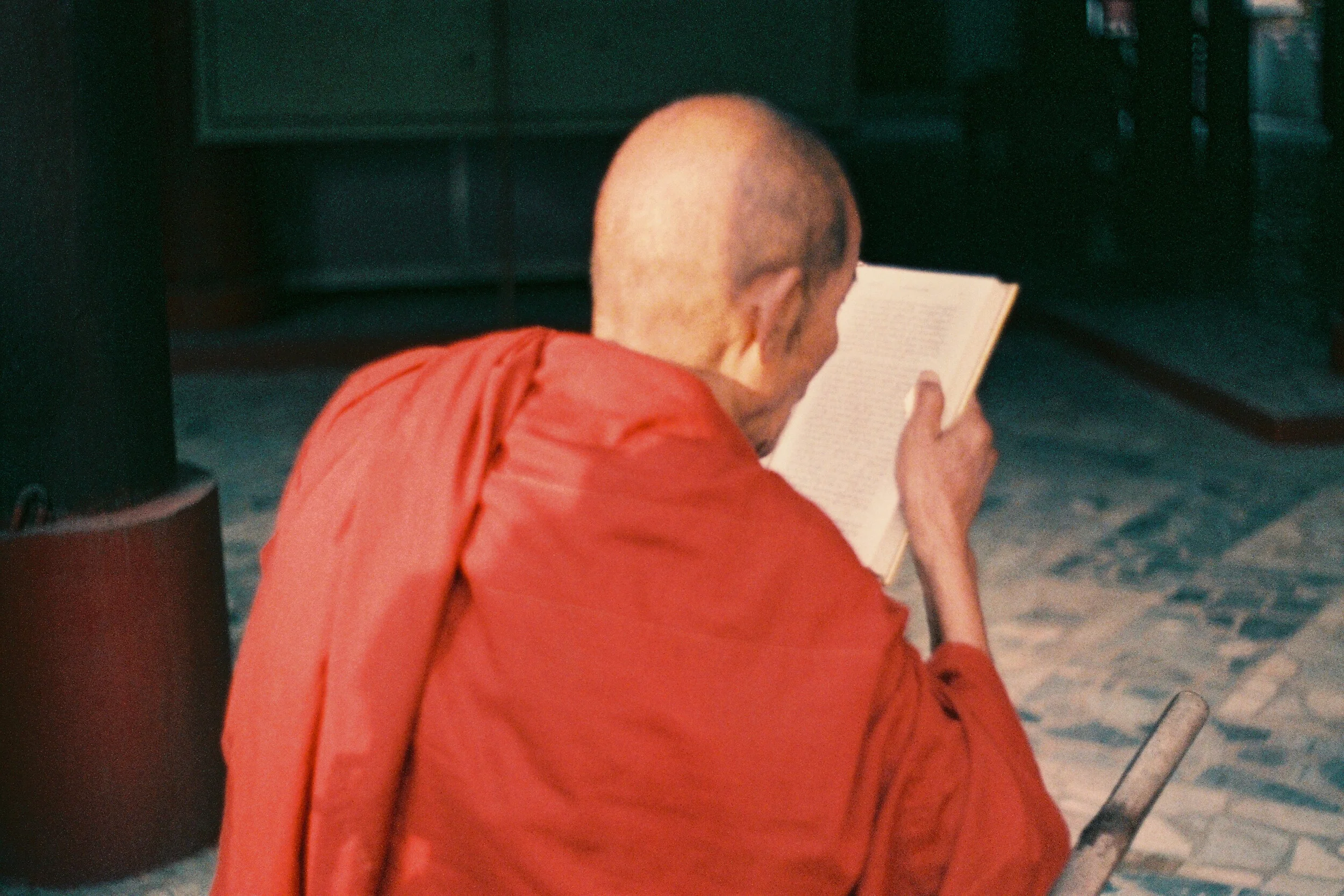

Photo by sergey neamoscou

The last brick of my professional path has taken me to IARAN, the Inter-Agency Research and Analysis Network, a collaborative hub, or think-to-do tank that advocates for a better strategic humanitarian system.

While I have followed humanitarian affairs before, it is my first time concentrating solely in the topic. However, taking into account my past life-experiences, plus the inputs I have received so far at IARAN, I have a much more informed -and critical- opinion about the humanitarian sector and I would like to share it with you.

Humanitarian aid in itself comes from a genuine and noble idea of helping people affected by crises. Nonetheless, it has grown to be based on unequal and neocolonialist practices. Why do I think this?

Well, during the process of its development and its adaptation to a system, the money for aid has increased billions, and since the first big aid agencies were of western origins, the concentration of said resources have historically stayed in a small number of Western actors.

At the beginning this made sense because the first catastrophes that were systematically assisted happened in Europe. Nevertheless, as years passed by, while crises moved from the European continent to other latitudes, aid money didn’t. To this day, humanitarian assistance- just to mention a random example, in Ethiopia- is still coordinated (imposed) in (by) the West.

Apart from the fact that money destined for humanitarian aid is staying away from crisis-affected people, the Machiavellian element here is that there are people getting richer and richer -as you read these words-, who are supposed to be dedicated to help others in need. We can say that I understand (not justify) how and why the system works like that, but I just can’t wrap my head around someone getting rich on behalf of other people’s misery.

I don’t think that you should sell your expertise and labor force for free (believe me, I was an intern at the United Nations), but what makes it astonishing is that humanitarians sitting in cozy Geneva, earn way more and have more decision-making power than humanitarians who are on the frontline in crisis-affected countries. Not only salary-wise but they also have more benefits.[1]

This happens even in the case where the international humanitarian and the local humanitarian have the same education, the same experience, but not the same contextual understanding and local knowledge; the local humanitarian wins there, hence it is more valuable, but worse payed[2].

Just for the fact of being a local worker makes it more probable to be attacked during an armed conflict for example. In fact, in 2018, worldwide, 93% of attacks against humanitarian actors were against local ones[3]. In a country like Colombia, my birthplace, targeting a local humanitarian would be easier, less mediatic and the probability of being held accountable is minimum. Just in 2018, 110 Colombian Human Rights defenders were killed.[4]

When “southerners” (as you read it on the literature), like me, try to apply for these jobs, we are immediately stopped by: “If you don’t have an EU passport, or a work permit to work in__________ (fill in the blank with any European country) do not proceed. Whereas for Northerners, going to work in our countries is a piece of cake (while getting better payed than locals while at it).

Now, going back to local knowledge and contextual understanding, the mentioned neocolonialist approach doesn’t concentrate alone on the money situation. For instance, I worked on peace-development projects in two conflict zones of Colombia, Catatumbo and Arauca; at this time we tried to train leaders and emphasize on local particularities as added values in order to better create a culture of peace in two of the most war-affected regions in the country.

Here, I was an eyewitness of the arrogant way in which locals are addressed by some international organizations or international cooperants. Even if they employed political correctness as their speech, their non-verbal language was very telling:

While discussing what the local community considered important for peace in one of the most affected regions in a long-lasting armed conflict, the international actors avoided the conversation by concentrating on the fact that there were no women on the panel. Their attitude was almost saying: “convince me that you’re “good” and if you fit in my definition of being “good”, I will agree to help you.”

While the local NGO I was working with had more access to vulnerable zones, it was normal to stop seeing international actors. After seeing what I just mentioned, I understood why. Partnership and trust-building was almost zero. International NGOs were sent there to evaluate, judge, and not to help.

Don’t get me wrong, I think gender equality is an aim in itself and it should be something to address, but it should not be reduced to such simple factors. You might’ve expected that after so many failed examples, international actors would have understood by now that it is counterproductive to try to build bridges, with crisis-affected people outside the West, by not asking any questions, by imposing things, and by bringing airs of moral superiority.

Actually, there is even some kind of instrumentalization of the locals coming from international NGOs. By working on another international organization in Colombia, I noticed how locals are there to give information, interviews, etc. and once the required data is received, there is no type of accountability or follow-up. At the end, telling a researcher about how many coca crops are there, how many murders there have been, and all sorts of sensible information, doesn’t bring any help from the ones asking the questions.

That information is used by international organizations to draft reports, those reports are used to convince donors, donors are used to earn money, and the majority of that money stays there. A system that is supposed to help people, collects a lot of money that never actually reaches people.

With this I am not saying that humanitarians are evil, that they shouldn’t exist or that all local crises can only be solved locally. I am quite aware that humanitarian assistance around the world is vital for the survival of several communities (Palestinians, Saharawi, Rohingya, for instance); that reports are essential for understanding, assessing and denouncing crises; and that the humanitarian community intends to make the world a better place. However, I would advocate for a more inclusive, diverse and development-oriented humanitarian system.

Giving assistance is not only about getting to crisis-affected regions, give one pound of rice, one bag of cement, a doctrine and leave. The humanitarian thing to do is to put solidarity as the main engine of interactions between aid organizations and people; to diversify the sector by working together with local NGOs and locals as equals; and to partner-up with crisis-affected populations by giving them influence over the decisions that will later affect them.

By Juan Sebastián Brizneda Henao

REFERENCES

[1] Carr, S & McWha-Hermann, (2016) I. Mind the gap in local and international aid workers’ salaries. The Conversation. http://theconversation.com/mind-the-gap-in-local-and-international-aid-workers-salaries-47273

[2] IARAN (2018) From Voices to Choices Expanding crisis-affected people’s influence over aid decisions: An outlook to 2040. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/593eb9e7b8a79bc4102fd8aa/t/5be216ff562fa77a941b14eb/1541543685634/Voices2Choices_FINAL-compressed.pdf p29

[3] Gutiérrez, I & Marí, J (2018) El 93% de los cooperantes humanitarios atacados en 2018 eran trabajadores locales; El Diario. https://www.eldiario.es/desalambre/victimas-ataques_0_939306361.html

[4] United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (2019) Situation of human rights in Colombia, https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/G19/025/43/PDF/G1902543.pdf?OpenElement