The international aid system is facing an unprecedented crisis. According to the Humanitarian in 2030 report by IARAN, the traditional model of international NGOs (INGOs) is set to undergo radical transformation, if not disappear entirely. Shrinking public funding, growing pressure to localize aid, and the rise of local or hybrid actors mean that yesterday’s paradigms no longer hold. In a world where humanitarian aid is becoming polycentric, fragmented across sino-humanitarian models[1], religious solidarity systems, competing geopolitical blocs, and autonomous local networks, HR functions must adapt to a decentralized ecosystem logic.

In this context of upheaval, organizations have no choice but to profoundly rethink their positioning, modes of action, and structure. The outsourcing of the HR function is part of this dynamic. It is not merely an administrative solution but a response to major structural challenges. It forms part of a strategic reflection on the NGO’s value chain, enabling each organization to refocus on its core mandate and unique areas of expertise: in essence, on what justifies its existence.

This fundamental shift was already anticipated by Rosabeth Moss Kanter in the foreword to Human Resources in the 21st Century (2003). She predicted not the disappearance of HR, but its redefinition: HR tasks would still exist but would be performed elsewhere, differently, often outside the organization. Today, this prediction resonates particularly strongly with INGOs undergoing profound transformation.

1. Outsourcing HR: A Deliberate Strategy, Not a Stopgap Measure

HR outsourcing should not be seen as a mere reaction to temporary difficulties. It is part of a broader logic of organizational transformation and adaptation to the new environment faced by NGOs. In a sector marked by unstable funding, increasing operational complexity, and growing professionalization demands, organizations need flexibility, responsiveness, and strategic control. It also enables them to comply with specific political or cultural frameworks in an increasingly polarized humanitarian landscape.

Outsourcing HR is a deliberate choice for specialization: entrusting certain functions to external providers allows NGOs to focus on their primary mission—implementing programs with strong social impact. This decision reflects a proactive organizational mindset, one that seeks to rethink its internal architecture to better meet tomorrow’s challenges. It is also a tool for resilience in scenarios such as the Age of Fortresses, one possible world described by the Future of Aid 2040 project, marked by border closures, the decline of multilateral cooperation, and the abandonment of vast crisis zones. In such an environment, only flexible, locally rooted HR structures, capable of operating without centralized institutional support, can maintain operational continuity. These projections raise deep questions about the sustainability of current HR models: what will HR look like in a world where humanitarian aid is no longer universal, but circumstantial and territorial?

2. Why Outsource? Cost Control, Agility, and Quality

One of the primary arguments for outsourcing is cost optimization. HR management involves significant fixed costs (salaries, tools, legal expertise), which can become difficult to sustain for organizations dependent on volatile funding. By outsourcing, NGOs convert these fixed costs into variable ones, enabling them to better adapt to budget fluctuations.

But the question is not purely financial. Outsourcing also offers valuable organizational agility. It allows NGOs to rapidly mobilize HR resources tailored to local contexts or emergency phases, access up-to-date expertise, and respond effectively to one-off or complex needs. This is especially relevant in scenarios of regionalization or aid fragmentation, where contextual responsiveness becomes a key asset.

Finally, the quality of HR services is often enhanced. Specialized providers have advanced tools, updated systems, and deep knowledge of legal and regulatory environments. They also bring an external perspective, often more neutral, that can help diagnose dysfunctions and improve internal practices.

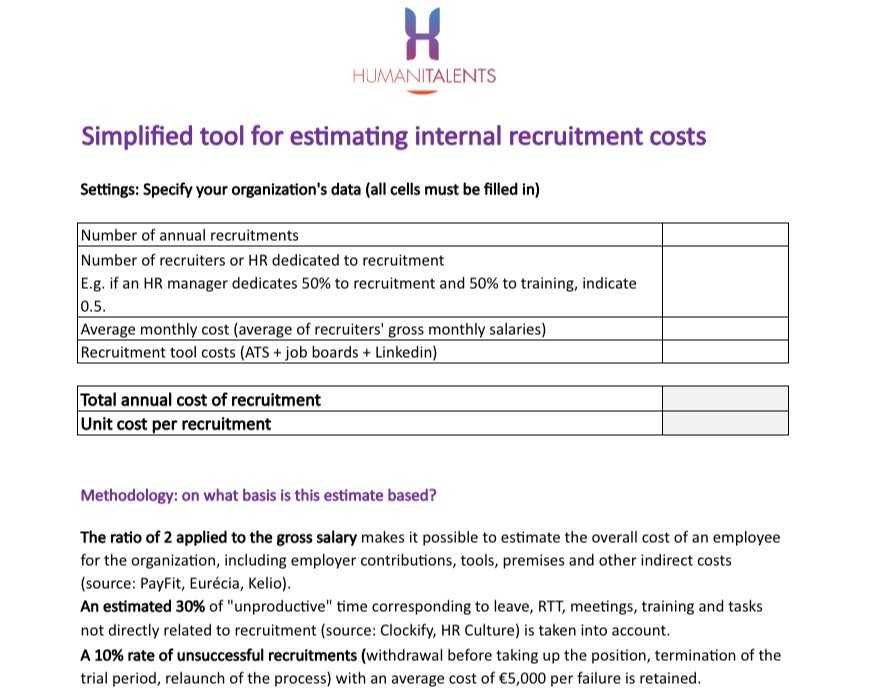

Humanitalents has developed a simplified estimation tool to help assess the overall cost of internal recruitment a cost[2] that is often underestimated or difficult to identify:

3. Which Functions to Outsource?

Not all HR functions are equally suited to outsourcing. Those with a high administrative or technical component are generally the first candidates. Payroll management and personnel administration (contracts, social declarations, file management) can be outsourced effectively.

Recruitment Process Outsourcing (RPO) can cover the entire process: from defining needs to the final selection of candidates. This approach can sustainably lighten internal processes while ensuring a better fit between recruited profiles and the sector’s evolving requirements.

Support services for field missions, such as centralized HR help desks, also help streamline interactions, especially in remote or disconnected environments. More specialized functions, such as mentoring, HR audits, psychological support for teams, or continuous training, can also be outsourced, particularly when the required expertise is scarce internally or the needs are occasional. In the future, inter-NGO shared services models, regional HR consortia, or outsourcing driven by local actors may well emerge.

The key is to clearly define what is delegated and what remains at the core of internal HR governance to ensure coherence and continuity.

4. Outsourcing and Decentralization: A Strategic Tandem

In a context of budgetary pressures, aid fragmentation, and humanitarian sector reconfiguration, decentralization is becoming a strategic lever for NGOs. By moving certain decision-making closer to the field, organizations can gain relevance, agility, and efficiency.

Within this dynamic, the decentralization of certain HR functions emerges as a natural evolution. Recruitment, in particular, lends itself well to this approach. Granting field missions greater autonomy to manage their recruitment, within a common framework defined by headquarters (e.g., through a charter including principles of non-discrimination and transparency), combines proximity, execution speed, and respect for organizational values.

This evolution is part of a broader trend: more and more organizations are rethinking contractual status. Some positions are now opened without prior distinction between "expatriate" or "national" contracts, using differentiated packages based on profiles, while adhering to a shared localized contract approach.. This trend, already observed in some large NGOs, could soon become the norm, further reinforcing the need for decentralized, flexible, and contextualized HR solutions.

Decentralization allows missions to draw on external expertise while maintaining alignment with organizational standards. Outsourcing at this level becomes a lever for agility and performance, while enabling costs to be charged directly to project budgets rather than often-constrained central HR lines.

Combining decentralization and outsourcing allows missions to equip themselves flexibly and contextually while maintaining a common strategic direction, an increasingly decisive balance for preserving NGO impact and responsiveness in an ever more fragmented environment.

5. What Role for Internal HR in an Outsourced Model?

Outsourcing does not mean the disappearance of internal HR teams. On the contrary, their role becomes more strategic than ever. Freed from the most operational or administrative tasks, internal HR functions can focus on higher value-added missions aligned with the organization’s mandate and the demands of the humanitarian context.

The first role of internal HR is to act as the custodian of HR strategy: setting broad talent management orientations, defining medium- and long-term objectives, monitoring key indicators, and ensuring that all HR actions, whether internal or outsourced, remain aligned with the organization’s values and priorities.

HR teams also play a key role in employer branding: a crucial issue in an increasingly competitive humanitarian talent market. This involves clearly communicating organizational values, highlighting potential career paths, and emphasizing the meaningfulness of the work.

Another essential responsibility is onboarding and career management. Recruitment is only the first step; employees must then be supported, trained, and helped to grow within their roles and the organization. This requires proactive management of skills, mobility, and professional development.

Internal HR must also foster effective staff dialogue and internal communication—vital for cohesion, trust, and staff engagement, even in the most challenging contexts. Additionally, they must regulate: ensuring ethical consistency, vigilance over psychosocial risks, and monitoring collective dynamics: including in multicultural and geographically dispersed environments. In this way, they become architects of adaptive human ecosystems, ready for uncertain futures , not merely administrators.

In short, HR services do not disappear in an outsourced model, they are reinvented as strategic pilots, guardians of organizational meaning, and catalysts for transformation.

Conclusion

Given the transformations underway in the humanitarian sector, HR outsourcing should not be seen as a defensive choice, but as a structural response to the growing complexity of aid. It enables INGOs to strengthen their impact while adapting to increasingly diverse geopolitical, operational, and human realities.

But what will HR functions look like in a world where humanitarian aid is shaped by competing empires, community networks, or inward-looking fortresses? This is no longer a theoretical question; it already informs discussions between Humanitalents and some HR Directorss. It is also at the heart of a global foresight exercise, Future of Aid 2040, whose preliminary results, based on more than 800 contributions, outline four possible futures for the humanitarian system. The full report will be published in September 2025. In the meantime, these scenarios already invite each organization to test the robustness of its structural choices: starting with its HR function. Because in all possible futures, one constant remains: the ability to attract, support, and grow talent will remain the key to relevant, ethical, and sustainable aid.

[1] The term "Sino-humanitarian models" refers to aid strategies developed by the People's Republic of China, marked by centralized state control, non-interference in political or democratic governance of recipient countries, and alignment with China's broader geopolitical interests. These approaches typically emphasize bilateral agreements, large-scale infrastructure investments, and an expanding presence particularly across Africa and Asia.

[2] This tool provides an initial reference point to start a conversation, because you can only manage effectively what you measure. It is not meant to replace a detailed financial analysis: a more precise evaluation would require in-depth work that considers the specific characteristics of each organization.

Bibliography

Center for Global Development. China’s Foreign Aid: A Primer for Recipient Countries, Donors, and Aid Providers. Washington DC: Center for Global Development, 2020. Disponible sur : https://www.cgdev.org/publication/chinas-foreign-aid-primer-recipient-countries-donors-and-aid-providers.

Chatham House. China’s Overseas Humanitarian Action to Assist Refugees. Londres: Chatham House, 2022. Disponible sur : https://www.chathamhouse.org/2022/06/chinas-overseas-humanitarian-action-assist-refugees.

Effron, M., Gandossy, R., & Goldsmith, M. (dir.). Human Resources in the 21st Century. Hoboken: Wiley, 2003.

IARAN. The Future of Aid: INGOs in 2030. Londres: Inter-Agency Research and Analysis Network (IARAN), 2016. Disponible sur : https://iaran.org/s/the_future_of_aid_ingos_in_2030.pdf.

IARAN. Future of Aid 2040: Pathways to Transformation. Paris: IARAN, 2025. Disponible sur : https://iaran.org/future-of-aid.

Kanter, R.M. ‘Foreword’ in Effron, M., Gandossy, R., & Goldsmith, M. (dir.), Human Resources in the 21st Century. Hoboken: Wiley, 2003.

Meier, P. Digital Humanitarians: How Big Data Is Changing the Face of Humanitarian Response. Boca Raton: CRC Press, 2015.

The CALP Network. The Future of Financial Assistance: An Outlook to 2030. CALP, 2019. Disponible sur : https://www.calpnetwork.org/publication/the-future-of-financial-assistance/.

World Economic Forum. 5 Futures for Aid in a Divided World. WEF, 2025. Disponible sur : https://www.weforum.org/stories/2025/04/5-futures-for-global-aid/.